Monitoring Results

Vegetation monitoring is crucial for measuring the health of tidal wetlands over time. Understanding how and when vegetation establishes in restoration sites is key for tracking restoration success, determining when other important species’ habitats might form, and quantifying the impact of invasive species.

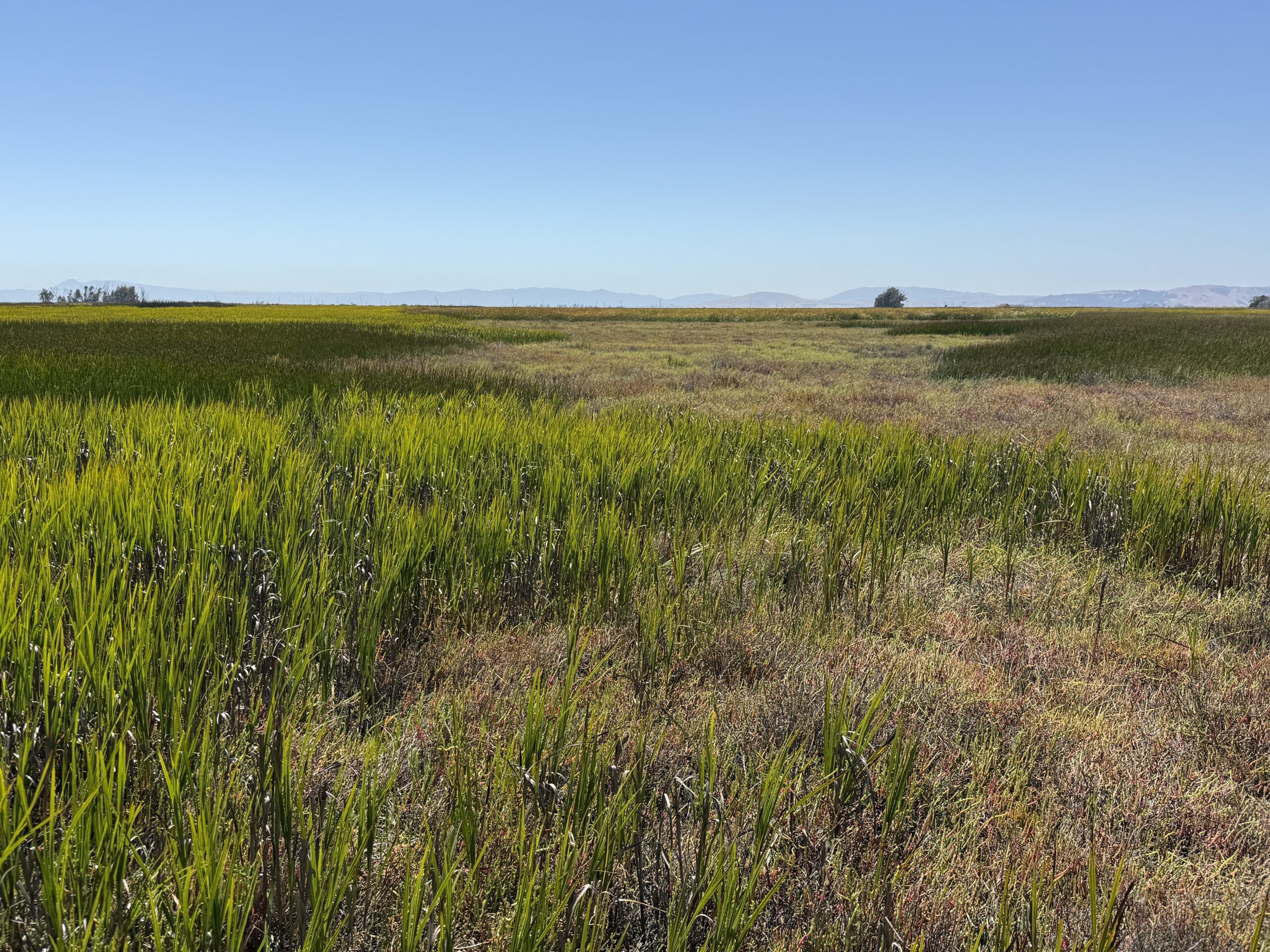

Wetland vegetation establishment is key to tidal wetland restoration success. Plants provide habitat and food for birds, mammals, and invertebrates that live in or migrate through wetlands. Wetland plants slow waves, helping protect shorelines from flooding and erosion, and trap sediment from tidal waters, which helps wetland elevations keep pace with rising seas. Wetland plant species have evolved to thrive in constantly wet and varying salinity conditions, with plant diversity increasing as salinity decreases. Because plant material decomposes very slowly under persistently wet conditions, wetlands are capable of storing more carbon in the soil per unit area than any other ecosystem.

Challenge & Response

In order for tidal wetland plants to establish and thrive in restoration sites, certain environmental conditions must be in place. If the wetland surface elevation is either too low or high, wetland plants will not grow because they are either inundated for too long or not long enough. Depending on the plant species, the presence and concentration of salinity can restrict or prevent growth. Plants also cannot grow if the sediment is too dense (clay) or too loose (sand). There is therefore a delicate balance in wetland restoration to create the most ideal conditions for successful plant establishment and appropriate diversity based on the location in the Estuary.

Restoration practitioners can address these issues in several ways. Channel networks can be created prior to tidal restoration to ensure proper tidal flow and drainage. Wetland elevations can be raised using dredge material, or heavy equipment can be used to lower the elevation to ideal ranges for vegetation establishment.

Science Framework

Establishment of vegetation in a wetland restoration project sets the stage for bird and mammal use and shoreline resilience.

- Are changes in tidal marsh ecosystems impacting water quality?, What new information do we need to better understand regional lessons from tidal marsh restoration projects, advance tidal marsh science, and ensure the continued success of restoration projects?, Where and when can interventions, such as placement of dredged sediment, reconnection of restoration projects to watersheds, and construction of living shorelines, help to sustain or increase the quantity and quality of tidal marsh ecosystems?

Key Metrics & Figures

Plant community monitoring through the WRMP happens at multiple scales: landscape level through the Baylands Habitat Map 2020, regional level through the California Rapid Assessment Method (CRAM), and the site level through plot-based vegetation surveys.

Looking for local data and information?

Metrics describe how the WRMP conducts science to better understand and monitor the Estuary’s tidal wetlands, like water quality, fish habitat, wetland condition, and benefits to humans. Explore all the WRMP’s metrics, which aim to guide wetland management and restoration.

How We Monitor

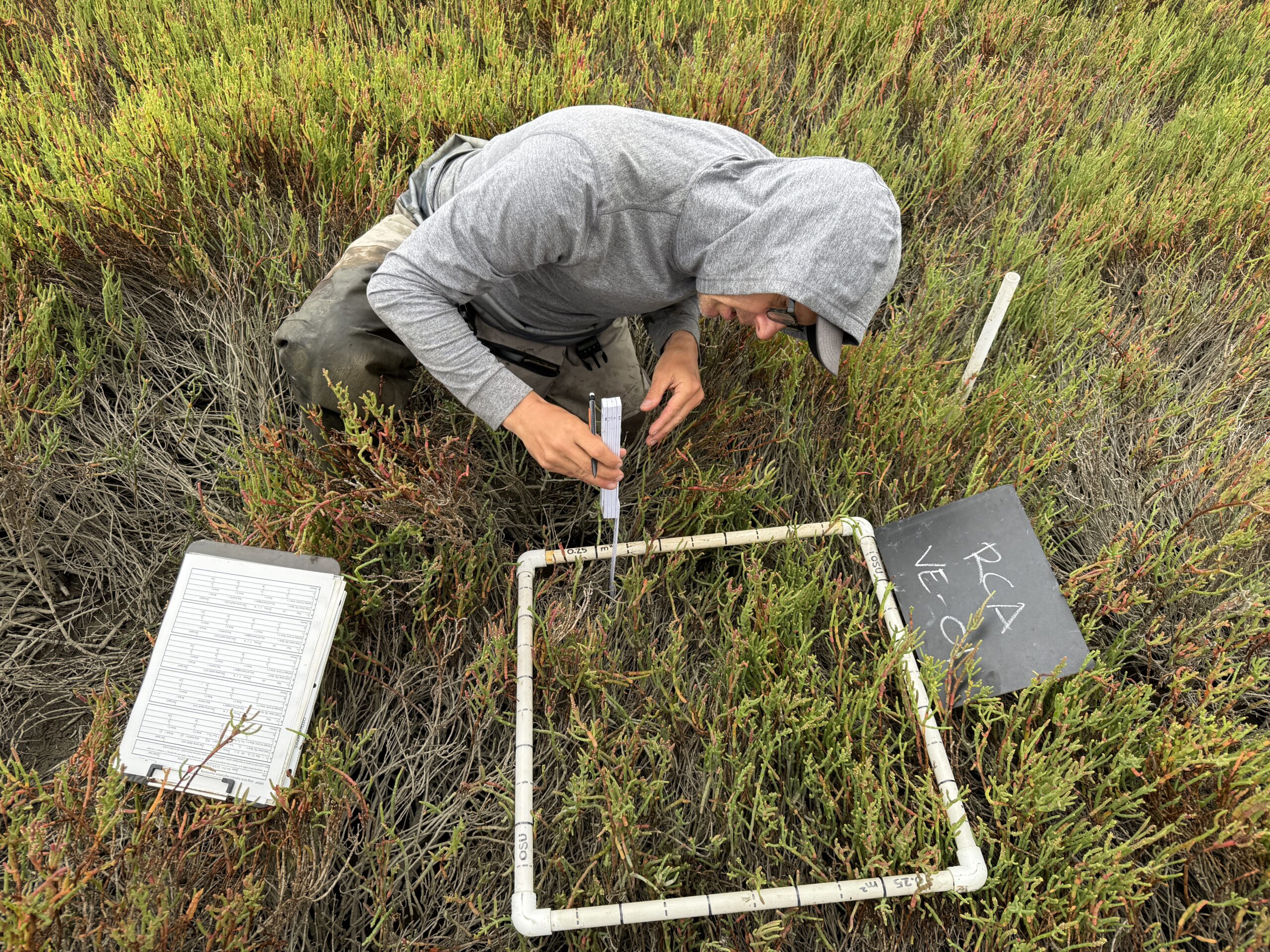

At the site level, the WRMP monitors plant community change over time through fixed plot-based measurements within the tidal wetland and along transitions with upland and channel edges.

1

- Track trends in plant diversity and distribution across the Estuary to understand how they adapt to changing conditions.

- Monitor how plant diversity in restoration sites changes with age and location relative to mature wetlands.

- Track changes in invasive species abundance and distribution.

2

- Plant identity, abundance, and invasive status over time in plots distributed across WRMP sites.

- Plant height to compliment bird habitat monitoring.

- Environmental data such as salinity and water depth to help explain plant distribution.

3

- At Benchmark, Reference, and Project tidal wetland sites from Suisun Bay to the Lower South Bay.

- 30 plots are sampled during every sampling event at each site, and repeated at those same locations over time.

A key way to track how plant community distribution and composition change over time is by monitoring at fixed locations across a tidal wetland. Dr. Chris Janousek, a senior researcher at Oregon State University, is leading work to establish long-term tidal wetland plant monitoring at an initial 18 sites across the WRMP’s monitoring network. Plots at historic tidal wetland sites (Benchmark sites) across the Bay characterize plant communities in sites that have minimal human impact and provide examples for restoration site trajectories. Monitoring plots at older restored wetlands (Reference sites) shows how restored wetlands are maturing over time. Of key importance to restoration managers and regulators is monitoring how newly restored tidal wetlands (Project sites) are evolving and tracking locations where tidal elevations are high enough for plants to establish. Monitoring plant communities at the same location over time also helps to document if invasive species are spreading across the Bay and whether wetlands are keeping pace with sea-level rise, since changes in species composition and habitat loss can be early warning signs of ecological degradation.

One key management and monitoring question of the WRMP is understanding how tidal wetlands across San Francisco Bay are responding to changes in sea level and other environmental changes. Drs. Michael Vasey and Tom Parker, emeritus faculty from San Francisco State University, are setting the stage for understanding how plant communities along the wetland-upland and wetland-channel edges, called transition zones or ecotones, are changing over time as sea levels rise. This is important because previous studies of West Coast tidal wetlands show that much of a tidal wetland’s plant diversity is found along these ecotones. As sea levels rise, tidal wetlands can slowly move upland as areas that were previously not tidal become so. However, plants along the channel edges are likely to erode or drown. It is important to understand the rate at which this is happening, and tracking plant communities is a clear and indicative way to document these changes.